Mormon Wayfinding

It’s hard to get lost in Utah towns and cities.

June 13, 2019

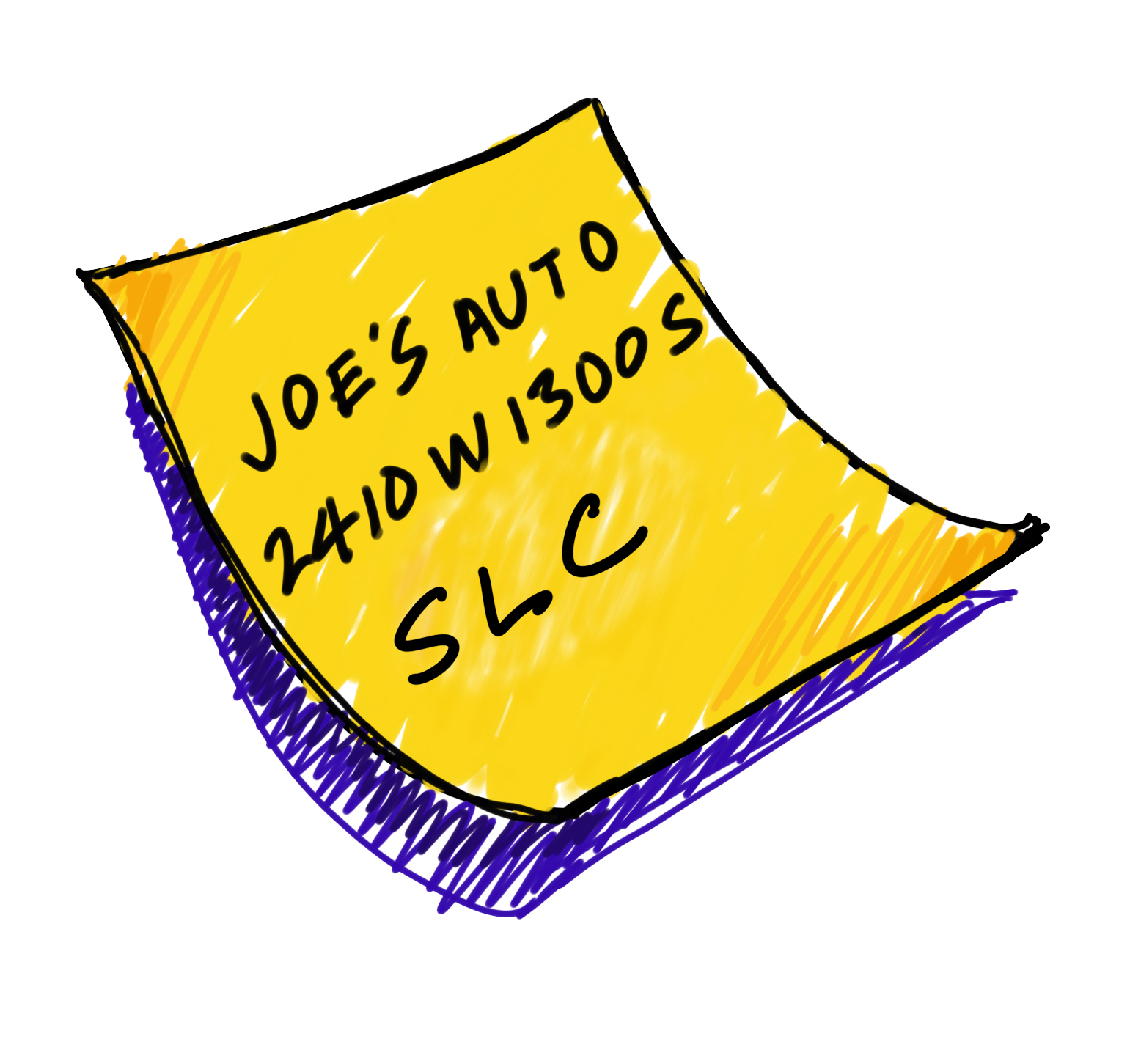

That is, after you learn the somewhat unusual system of street names and numbers. Your friend might live on North 9th West and work on West 18th South, or the restaurant might be at 4310 N 1800 E. All streets with west in the name curiously run north/south. North Temple street runs east/west, not north/south and is parallel to, not a continuation of, South Temple, a different street one block to the South. And so on. Yes, Utah towns can be confusing at first, but are wonderfully logical and learnable.

What Mormon city planners worked out in the mid Nineteenth Century, even before Utah statehood, is a perfect and rational X-Y grid system of identical square blocks organized around a center point, or in the case of Salt Lake City, a central single block, Temple Square. Parallel numbered streets ascend from the center in all four directions of the compass—First, Second, Third, etc., in concentric squares. So you have four Second streets and four Twenty-second streets and four everything streets – sounds nuts, right? No. Every number name is followed by a direction name: Second North, Third South, 2400 West and so on, signifying how far the street is from ‘0,’ or the town’s central axis. Therefore, Tenth West is a north/south street ten blocks west of the north/south center axis. Street names are expressed by locals in words (Ninth West), or more formally, in numbers, 900 West. So, built into the street name is how far it is from the center of town – Sixth South, or 600, is near downtown; 4400 South is not.

So that’s the X. What about the Y? Here is where it can get confusing. Address numbers on each street are followed by, yes, a direction name or letter that together with the street name tells you how far from the other central axis you are and in which direction. So, 4310 N 1800 E is on the north/south street eighteen blocks east of the center (X axis) and about forty-three blocks north of the Y axis.

And no messy avenue and street sub-names are needed for differentiation. First North, Third West, Twenty-sixth South; nobody in Salt Lake says 9th Street or 21st Avenue; no one includes the words street or avenue in writing or speech. Refined in writing to numbers and letters only, 682 W 400 N and 1290 N 700 E, for example, the method works exceptionally well in most media and is easily learned and used by visitors. Yes, difficult to describe the system in words but once you get it, you’ve got it forever. And with the generally neat and same sized blocks of most Utah towns, this coldly logical addressing system is among the most efficient in the world.

And no messy avenue and street sub-names are needed for differentiation. First North, Third West, Twenty-sixth South; nobody in Salt Lake says 9th Street or 21st Avenue; no one includes the words street or avenue in writing or speech. Refined in writing to numbers and letters only, 682 W 400 N and 1290 N 700 E, for example, the method works exceptionally well in most media and is easily learned and used by visitors. Yes, difficult to describe the system in words but once you get it, you’ve got it forever. And with the generally neat and same sized blocks of most Utah towns, this coldly logical addressing system is among the most efficient in the world.

A real benefit to the overall approach is the built-in city-wide spatial orientation that comes from an X-Y system; each address quickly communicates generally where it is the urban layout – which quadrant and distance from center. A mathematician’s paradise and a wayfinder’s ideal. It’s not a romantic or colorful approach to names and numbers, but you will not get lost.

The tradeoff for this rational system is, of course, artlessness. No poetry, no locally-descriptive nomenclature, no nonsense. In Utah you’ll not find a Sunset Boulevard, a George Washington Parkway, a Columbus Avenue, a Bourbon Street, an Orange Grove Boulevard, a Constitution Avenue, or a Peachtree Street. History, local color, regional vegetation, unique topography and other interesting sources for naming streets are shunned. Mormon planners were not thinking about branding or placemaking or marketing new houses in suburban developments.

This rational and efficient system could only have been developed in a ‘clean sheet’ urban planning environment. That is, planners needed acres of flat undeveloped land unencumbered by historic roads and well-known public paths in order to create such an orderly and ideal program. In the 1800s in most emerging Utah towns empty land was first double bisected by two intersecting primary streets—a north/south Main street and an east/west Center street, thus setting up the perfect bi-systematical, four quadrant X-Y model. Laying out the grid of numbered parallel streets in all four directions completed the scheme. Go to nearly any town in Utah and check it out. From Provo to Payson to Panguitch, they’re all the same. A common and universal (to Utahans) wayfinding language.

Contrast this planning idealism with the eclectic street layouts of older and eastern cites that emerged organically over the centuries. Boston is based on Seventeenth Century carriage paths; suburban Virginia on winding colonial roads. Or compare with cities built around natural geographic features of rivers, lakes or extreme topography (Pittsburgh, Chicago, San Francisco). Only in the West, where planning often preceded development, could the idealistic Utah approach be implemented.

So next time you find yourself in Utah, take note of the gold standard in rational street naming and addressing. And if you want the best pizza in Salt Lake City go to 260 S 200 W.